The San Francisco Chronicle is reporting that once again, San Francisco Department of Public Works crews are undertaking the arduous task of removing sand from the Great Highway adjacent to Ocean Beach.

No matter how many times work crews clear it off the Great Highway and the adjacent pedestrian promenade at the city’s western shore, it keeps coming back.

“It’s a regular cycle,” said Mohammed Nuru, deputy director of the San Francisco Department of Public Works.

As it does every year, the city will undertake a major project to remove sand from Ocean Beach, and the adjacent walkway and highway between Noriega and Santiago streets in the Outer Sunset, and relocate it a bit south to shore up an eroding seawall.

Anyone that visits the SF Zoo or the beach knows there are dunes everywhere, but where does all that sand come from?

Some of it is just ordinary beach sand eroded from the sandstone cliffs near Fort Funston to the south. These cliffs are the exposures of a pair of rock formations geologists refer to as the Merced and the Colma.

These sandstone formations are relatively young (1.8-0.01 Myo.), and stretch down the peninsula coastline from Lake Merced to just past Mussel Rock. Because they’re weak, Pacific winter storms regularly chip away at the cliff faces, causing landslides threaten to carry parts of Daly City’s subdivisions to the beaches below.

Interestingly, the rest of the sand actually comes from a source 100 miles to the east and 16,000 years in the past: the Sierra Nevadas.

Back during the last glacial period, around 20-16 Kya, glaciers ground down the granite rocks that make up the Sierra, and seasonal melt waters fed those sediments to the tributaries of a Pleistocene Era Sacramento River.

However, back then sea levels were considerably lower, on the order of 400 ft. lower, so while sediments nowadays get dropped into the Bay, the Sacramento would have been able to deposit its sediments onto a vast shelf of relatively dry land stretching out past the Farallon Islands, because there was no bay to flow into.

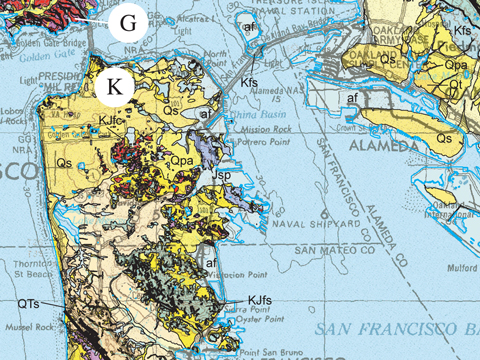

After the runoff floods receded, all that alluvial sand dried out, leaving it vulnerable to northerly winds which picked it up and carried it right back across the what is now the Bay Area, all the way to Oakland. Check out this portion of the USGS Geologic Map of The San Francisco Bay Region:

The areas marked “Qs” are Q(uaternary) s(ands). Nearly half of modern San Francisco sits on top of these ancient dunes. Visitors to Golden Gate Park and can see the residual hilly outlines of these ancient dunes. When Western San Francisco was built, there was no way to truck out all the sand, some of which had piled into dunes 60 ft. high, so they were stabilized with acres and acres of vegetation.

Examination of the sand reveals its origins in the Sierra Basolith. It’s composed of translucent quartzes; black magnetites (you did bring a magnet?); and if you’re lucky, even traces of gold. If you plan to mine it for Cash4Gold, the Department of Public Works can probably direct you to where they’d like you to start digging.

{ 0 comments… add one now }

You must log in to post a comment.